New Light

It is not easy to figure out the current developments in the visual and performing arts. Digitalisation has had a strong impact, providing new techniques and new artificial light sources. In recent years, installations, performances and productions with a strong emphasis on the use of light have been mushrooming. Also, the different categories have started to melt and merge and lose their distinctiveness. An immense new area of creative expression has opened up, where new art forms are teeming and seething, crawling and sprawling. Can we pinpoint the origin of this development? Is it possible to go back, get to the starting point and outline the history of the creative use of light? In the following I will try to do just that.

Strictly speaking, all forms of the aesthetic use of light may be considered “light art”: from the ritual use of open fires to the colourful window panes in gothic cathedrals to Rembrandt’s masterful usage of coloured pigments. However, all these examples make use of the light of the sun. This will not be our thematic priority, rather we will focus on the history of man-made sources of light. Thus, we will follow two threads that are distinctive and yet interwoven: first, the technical development of artificial light sources, and second, how these were used and modified for creative purposes.

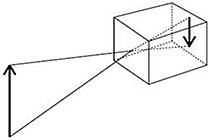

The original starting point may have been something the Greek philosopher Aristotle observed almost two and a half millenia ago: during an eclipse of the sun he discovered small bright spots in the shadow of a tree. These spots did not reflect the contours of the leaves but formed an image of the sun, and he deduced that these images had been created by the small “holes” in the foliage of the tree. In fact, rays of light shining through a small opening into a dark room – such as the shadow of a tree -create an image of the object that is emitting the rays. Because the rays cross at the entrance of the small hole, the image will appear upside down. Da Vinci also described this phenomenon, and in his era people already had “black boxes”, hand-made boxes with a small hole on one side, which could capture pictures. This kind of box was called “camera obscura”, and with a semitransparent backside the picture could even be viewed from the outside. Complete rooms were designed as dark, walk-in chambers, which could capture an image from the outside and make it visible on a white screen. However, this image could not yet be retained.

The original starting point may have been something the Greek philosopher Aristotle observed almost two and a half millenia ago: during an eclipse of the sun he discovered small bright spots in the shadow of a tree. These spots did not reflect the contours of the leaves but formed an image of the sun, and he deduced that these images had been created by the small “holes” in the foliage of the tree. In fact, rays of light shining through a small opening into a dark room – such as the shadow of a tree -create an image of the object that is emitting the rays. Because the rays cross at the entrance of the small hole, the image will appear upside down. Da Vinci also described this phenomenon, and in his era people already had “black boxes”, hand-made boxes with a small hole on one side, which could capture pictures. This kind of box was called “camera obscura”, and with a semitransparent backside the picture could even be viewed from the outside. Complete rooms were designed as dark, walk-in chambers, which could capture an image from the outside and make it visible on a white screen. However, this image could not yet be retained.

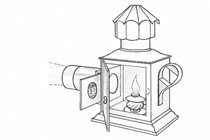

This was made possible by the “magic lantern”, the first device for projecting pictures, which was widespread in Europe from the 17th to the 20th century. The optical effect of projection is created by the opposite principle of the camera obscura: the “laterna magica” is a box with an opening on one side and a light source within – originally a candle or an oil lamp, later on an electric light source. The rays are guided through a collecting lens into the barrel-shaped lens tube. Between the box and the lens painted glasses may be inserted and can thus projected onto a screen. Thus, for the first time light could be used to create images, and these could even be set in motion by mechanic devices. This constituted the transition point between the natural and the artificial. In the second half of the 19th century the electric arc lamp was developed when Edison – after more than two thousand futile attempts – finally used a carbon filament to light up a glass bulb.

This was made possible by the “magic lantern”, the first device for projecting pictures, which was widespread in Europe from the 17th to the 20th century. The optical effect of projection is created by the opposite principle of the camera obscura: the “laterna magica” is a box with an opening on one side and a light source within – originally a candle or an oil lamp, later on an electric light source. The rays are guided through a collecting lens into the barrel-shaped lens tube. Between the box and the lens painted glasses may be inserted and can thus projected onto a screen. Thus, for the first time light could be used to create images, and these could even be set in motion by mechanic devices. This constituted the transition point between the natural and the artificial. In the second half of the 19th century the electric arc lamp was developed when Edison – after more than two thousand futile attempts – finally used a carbon filament to light up a glass bulb.

Following this line of development we will come across Joseph Niépce, a Frenchman who tried to retain the pictures of the camera obscura, not by drawing them, as many painters of the era did, but by fixing them onto light-sensitive material. In 1816 he succeeded in making the first prints with silver chloride paper, and ten years later he finally presented the first photograph ever: the view from this office, with an exposure time of eight hours!

Following this line of development we will come across Joseph Niépce, a Frenchman who tried to retain the pictures of the camera obscura, not by drawing them, as many painters of the era did, but by fixing them onto light-sensitive material. In 1816 he succeeded in making the first prints with silver chloride paper, and ten years later he finally presented the first photograph ever: the view from this office, with an exposure time of eight hours!

Of course, people and moving objects could not yet be photographed with this kind of exposure time. Together with his fellow countryman Daguerre, Niépce used a coated copper plate to achieve improved light sensitivity, and not much later the Englishman William Talbot succeeded in creating negatives which could be developed into positives. This was the starting point of the era of reproduction and photography. The next milestones were reached around the end of the 19th century: better lenses allowed shorter exposure times, the celluloid film was discovered, and as early as 1907 the brothers Lumiere developed the first colour photographs.

Instead of candles and oil lamps, artificial light sources were now being used for illuminating rooms, and artificial light was also introduced in the performing arts: theatre rooms and stage settings could be illuminated, drawing attention to the stage in general or to specific details. It was in the realm of photography that the first modifications became possible: the amount of light that impinges on the sensitive material is determined by aperture and exposure time. For many decades the photographers were the artists who used the electromagnetic vibrations of light as tools of creation in front of and behind the camera: handling an open aperture in a dark environment with moving lights finally inspired some artists to use the light bulb itself.

At first, no one realized the creative possibilities of moving a light bulb in front of an open aperture. Rather, it was used to reproduce a work routine, with small bulbs attached to the workers’ clothes so their movements could be determined in the finished picture.In 1889, Etienne Jules-Marey for the first time recorded the visible traces of light in this way.

At first, no one realized the creative possibilities of moving a light bulb in front of an open aperture. Rather, it was used to reproduce a work routine, with small bulbs attached to the workers’ clothes so their movements could be determined in the finished picture.In 1889, Etienne Jules-Marey for the first time recorded the visible traces of light in this way.

Although Jules-Marey did not regard his approach as an artistic endeavour, it marked the birth of “painting with light”, one of the most important forms of expression within this new artistic field.

Bragaglia, an Italian, introduced dynamic movement into photographic art in 1911: he asked illuminated models to move in front of his camera and used long exposure times to record the speed and direction of their movements.

Bragaglia, an Italian, introduced dynamic movement into photographic art in 1911: he asked illuminated models to move in front of his camera and used long exposure times to record the speed and direction of their movements.

In the 1930s, the Hungarian photographer Moholy-Nagy started to use semitransparent, diffractive objects, adding some kind of “brush strokes” created by flashlight. The American artist Man Ray started to literally paint with light by “writing” imaginary figures into space using a light bulb with a long cord. Due to the long exposure times the movement of the light bulb leaves bright traces on the film.

Several other artists also contributed their amazingly creative variations of art photography. Even Picasso felt inspired by the fascinating possibilities of a moving light bulb and its bright traces.

From the middle of the 20th century technological novelties turned up faster and faster. In Germany, Otto Piene became a pioneer of this new art form with handheld movable and mechanical light sources that he used for “ballets of light”. In 1963 the American artist Dan Flavin installed a naked yellow fluorescent light, using space itself for his artistic expression instead of modelling sculptures of light. Another American, James Turrell, created seemingly infinite spaces by combining large and evenly illuminated surfaces.

From the middle of the 20th century technological novelties turned up faster and faster. In Germany, Otto Piene became a pioneer of this new art form with handheld movable and mechanical light sources that he used for “ballets of light”. In 1963 the American artist Dan Flavin installed a naked yellow fluorescent light, using space itself for his artistic expression instead of modelling sculptures of light. Another American, James Turrell, created seemingly infinite spaces by combining large and evenly illuminated surfaces.

Refraction became the new rage. At the same time a new projection tool, the daylight projector, came into general usage and formed the basis of the “liquid light shows” of the hippies. In the glass dishes of the projector’s working area oil was mixed with water and colour. When the mixture started to move due to the heat from the projector the images created in this way were projected – via a deflection mirror – onto a screen, often as a choreography accompanying the psychedelic music of that era.

Originally used in advertising, the “living flames”, as neon lights are called in the United States, were introduced into art around the beginning of the 1970s. The thin, malleable tubes could be used for figures, words and sentences. Since the beginning of the 1980s Jenny Holzer creates neon signs with socially motivated messages, thus combining art with political statements.

Radical changes were brought about by the discovery of halogen light – a light source which differs from all the previous ones due to its extreme brightness and the extremely small radiating surface. Its potential for shadow theatre was simultaneously recognised by a Frenchman, an Italian and a Swiss: the silhouette could now be moved away from the screen and enlarged, without losing its sharp contour! This novel feature revolutionised traditional shadow play, turning it into shadow theatre. From now on all the available space can be used, even that in front of the screen. With this development the use of light has finally arrived on the stage and in the performing arts. Robert Wilson, the American “theatre artist”, illuminated the stages of the world with his stunning productions using complex lighting design to enthral his audiences.

Nowadays it is the laser – light amplified by stimulated emission of radiation – which supplies the most focused beam: light of a single wavelength, focused to a tight spot. Combined with sophisticated software programs, laser light shows entertain large audiences in the Western world, providing new artistic impulses

Nowadays it is the laser – light amplified by stimulated emission of radiation – which supplies the most focused beam: light of a single wavelength, focused to a tight spot. Combined with sophisticated software programs, laser light shows entertain large audiences in the Western world, providing new artistic impulses

.We will – for now – conclude this enumeration with the Polish artist Tadeusz Wierzbicki who added reflection as an additional variation. His philosophical productions with beams of light that are “bent” via movable mirrors capture audiences all over the world and his “light masks” – formed with slightly curved mirrors which seem to reflect grotesque faces – add new dimensions to international exhibitions.

Something nobody had realised at this point: two more revolutions were yet to come! Around the turn of the millennium the new technique of the light-emitting diode (LED) conquered more and more areas of life. The LED does not contain a filament but consists of a small crystal which radiates light when electricity flows through it. It emits less heat than conventional light sources and it is characterised by an extremely long lifetime. These characteristics have already helped establish the LED whose triumph has probably only just begun. Many creative artists have already made use of this new impulse – too many to name them all.

At the same time, the digital camera has revolutionised the field of photography. The integrated chip makes it possible to turn light into electric impulses and to store them. The “bulb function” complements the program menu of high-end digital reflex cameras: how long the aperture remains open is limited only by the battery’s capacity. This makes it possible to “paint” with light in a dark room as long as the artist may desire, and the sensor will record whatever light there is. A special software program offers the additional fascinating possibility to paint on a canvas in the dark and to record the painting.

Thus, the trace we have been following has finally reached our present time, and the ball which had been started rolling by Aristotle has landed at our feet. Our present in which we are flooded with media we are also endowed with fascinating new means of illumination and their detailed control. This great wealth is an invitation to create ever new images of light, to draw images from our own depths and give them visible form. After all, isn’t creating one of the things that give meaning to life?

And aren’t we – in last consequence – made out of light?

Aren’t we stardust?